Charting the Invisible: IMAP and the Quest to Map the Heliosphere

- Bryan White

- Jan 13

- 22 min read

Abstract

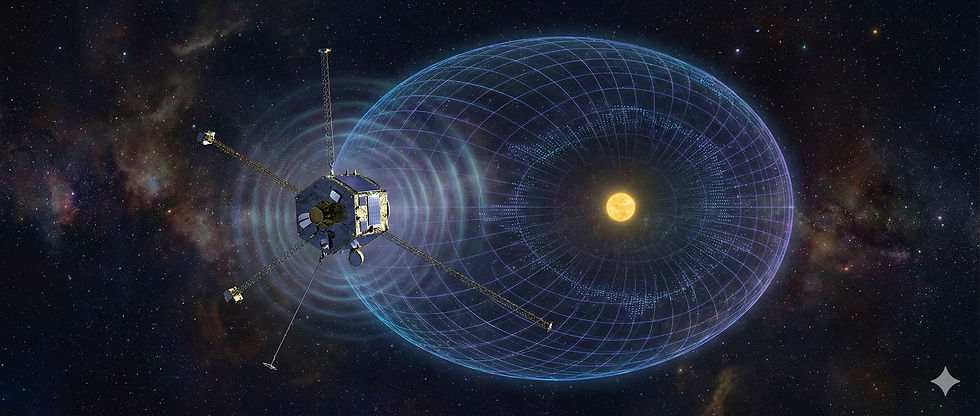

In the grand chronicle of space exploration, the mapping of the solar system’s outer boundaries represents a frontier that has shifted from the realm of theoretical conjecture to empirical observation only within the last half-century. On January 10, 2026, a new chapter in this exploration commenced with the successful orbital insertion of the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) at the first Sun-Earth Lagrange point (L1). This mission, a collaborative triumph led by Princeton University and the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), stands as a modern "celestial cartographer," poised to revolutionize our understanding of the heliosphere—the vast, magnetic bubble that shields our solar system from the harsh radiation of the galaxy. This report provides an exhaustive, multi-dimensional analysis of the IMAP mission. It traces the historical and scientific imperatives that necessitated such a probe, details the complex orbital mechanics of its L1 halo orbit, and conducts a deep-dive technical review of its ten-instrument payload. Furthermore, it explores the mission's dual mandate: to resolve the fundamental physics of particle acceleration and to serve as an operational sentinel for space weather, thereby safeguarding the infrastructure of a society increasingly dependent on space-based technologies. Through this detailed examination, we illuminate how IMAP will decode the "echoes" of the solar wind to reveal the invisible topography of our home in the cosmos.

Chapter 1: The Heliospheric Imperative

1.1 The Concept of the Cosmic Bubble

To understand the significance of the IMAP mission, one must first grasp the nature of the environment it studies. The sun is not merely a static ball of light; it is a dynamic engine that continuously exhales a stream of superheated, charged plasma known as the solar wind. This wind races outward in all directions at supersonic speeds, ranging from 300 to 800 kilometers per second. As it expands, it carries with it the sun's magnetic field, inflating a colossal bubble within the interstellar medium (ISM)—the tenuous soup of gas and dust that fills the void between stars.1

This bubble is called the heliosphere. It is not a perfect sphere but is shaped by the relative motion of the sun through the galaxy, likely elongated into a comet-like tail in the wake of our star's path. The heliosphere acts as a crucial cosmic shield. The ISM is permeated by galactic cosmic rays (GCRs)—high-energy particles stripped of their electrons and accelerated to near-light speeds by distant supernovae and other violent astrophysical events. Without the heliosphere, the flux of these damaging particles in the inner solar system would be significantly higher, potentially altering the atmospheric chemistry of planets and posing severe risks to life.1

The boundary where the solar wind's pressure is finally counterbalanced by the pressure of the interstellar medium is a complex, multi-layered region. It consists of the termination shock, where the solar wind abruptly slows from supersonic to subsonic speeds; the heliosheath, a turbulent region of compressed plasma; and the heliopause, the theoretical outer edge where solar material meets interstellar material.3 Understanding this boundary is essential for understanding the habitability of our own system and, by extension, exoplanetary systems orbiting other stars.

1.2 The Legacy of Voyager and IBEX

Our current picture of the heliosphere has been painstakingly assembled over decades. The twin Voyager spacecraft, launched in 1977, were the first human-made objects to physically touch these boundaries. Voyager 1 crossed the termination shock in 2004 and the heliopause in 2012, while Voyager 2 followed, crossing the heliopause in 2018.4 These crossings were historic, providing the first in-situ measurements of the plasma density, temperature, and magnetic fields in interstellar space.

However, the Voyagers provided only two "pinprick" data points in a vast, three-dimensional structure. Relying solely on Voyager data to map the heliosphere would be akin to mapping the entire Earth's weather system using only two weather stations—one in Greenland and one in Antarctica. While valuable, they could not reveal the global shape of the bubble or its temporal dynamics.6

The Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX), launched in 2008, attempted to remedy this by taking a global "picture" of the heliosphere. Instead of traveling to the boundary, IBEX orbited Earth and detected Energetic Neutral Atoms (ENAs)—particles that originate at the boundary and travel inward. IBEX revealed a feature that no theorist had predicted: a bright, narrow "Ribbon" of ENA emissions wrapping around the sky.7 This discovery upended existing models, suggesting that the interstellar magnetic field plays a much more dominant role in shaping our heliosphere than previously thought. Yet, IBEX’s cameras were low-resolution, leaving the fine details of this interaction—and the physical mechanism creating the Ribbon—shrouded in mystery.

1.3 The Scientific Case for IMAP

The scientific community recognized that a new mission was needed—one that combined the global imaging capability of IBEX with significantly higher resolution and sensitivity, while also acting as a high-fidelity in-situ monitor of the solar wind like the Voyagers (but at 1 AU). This need crystallized in the 2013 Solar and Space Physics Decadal Survey, which recommended a mission to "map the heliosphere" as a high priority.9

IMAP was selected by NASA in 2018 as the fifth mission in the Solar Terrestrial Probes (STP) program.10 Its mandate is twofold:

Fundamental Physics of Particle Acceleration: To determine how particles are accelerated to high energies in the heliosphere. This is a universal problem in astrophysics, applicable to everything from solar flares to supernova remnants.12

Global Heliospheric Interaction: To establish the global shape and structure of the heliosphere and how it interacts with the Local Interstellar Medium (LISM).2

By placing a state-of-the-art observatory at L1, IMAP can simultaneously measure the "input" (the solar wind leaving the sun) and the "output" (the ENAs returning from the boundary), allowing scientists to connect cause and effect in a way never before possible.

Chapter 2: The IMAP Mission Architecture

2.1 Mission Selection and Management

The selection of IMAP marked a significant commitment by NASA to heliophysics. The mission is Principal Investigator (PI)-led, a management structure that places a senior scientist at the helm of the mission's scientific vision and execution. For IMAP, this leader is Professor David J. McComas of Princeton University.1 McComas, a veteran of the IBEX and Ulysses missions, brings decades of experience in ENA imaging and plasma physics.13

The implementation of the mission—the actual design, construction, and operation of the spacecraft—is managed by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland.1 APL has a storied history in building robust spacecraft for extreme environments, including the Parker Solar Probe and the New Horizons mission to Pluto. This partnership ensures that the ambitious scientific goals set by Princeton are matched by the engineering rigor required to survive deep space.

The mission is part of the Solar Terrestrial Probes program, managed by the Explorers and Heliophysics Projects Division at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.14 It operates under a cost-capped model, which necessitates focused scientific goals and disciplined engineering trade-offs.

2.2 The International Consortium

While led by US institutions, IMAP is a truly global endeavor. The complexity of the scientific questions demands specialized instrumentation that no single nation possesses entirely. The mission team includes over 25 partner institutions from across the United States, Europe, and Japan.1

Poland: The Space Research Center of the Polish Academy of Sciences (CBK PAN) developed the GLOWS instrument, a critical component for measuring the distribution of interstellar neutral hydrogen.16

United Kingdom: Imperial College London provided the Magnetometer (MAG), leveraging their extensive heritage from missions like Cluster and Solar Orbiter.16

Switzerland: The University of Bern contributed to the design and testing of the ENA imagers, specifically IMAP-Lo, bringing expertise honed during the Rosetta mission.18

Japan: Nagoya University and other Japanese institutions participate in the science team, analyzing data to understand particle acceleration mechanisms.15

This international fabric enriches the mission, bringing diverse intellectual traditions and technical solutions to the challenges of deep space exploration.

2.3 Launch and Deployment

The journey of IMAP began on September 24, 2025.10 The spacecraft was launched aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 Block 5 rocket from Launch Complex 39A at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida.10 The Falcon 9, a workhorse of the modern space era, provided the necessary delta-v (change in velocity) to propel the nearly 900-kilogram spacecraft (wet mass) out of the Earth's gravity well and onto a transfer trajectory toward the Sun.10

The launch window and trajectory were calculated with immense precision. Unlike missions to low Earth orbit, which can launch nearly daily, missions to Lagrange points require specific timing to ensure the spacecraft arrives at the correct location with the correct velocity vector. The launch was a rideshare mission, carrying secondary payloads such as NASA's Carruthers Geocorona Observatory and NOAA's Space Weather Follow On L1 (SWFO-L1), maximizing the utility of the launch vehicle.20

Chapter 3: Celestial Mechanics and the L1 Orbit

3.1 The Physics of Lagrange Point 1

The destination of IMAP is not a planet or a moon, but a point in empty space: the first Sun-Earth Lagrange point (L1). Named after the 18th-century mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange, these points are solutions to the "three-body problem," locations where the gravitational forces of two large masses (the Sun and the Earth) and the centrifugal force felt by a smaller object balance each other perfectly.21

L1 is located approximately 1.5 million kilometers (about 930,000 miles) from Earth, directly along the line connecting the Earth to the Sun.21 At this specific distance, the gravitational pull of the Sun is partially cancelled by the gravitational pull of the Earth. Normally, an object closer to the Sun would orbit faster than Earth (Kepler's third law). However, the Earth's gravity pulls the spacecraft back, effectively slowing its orbital period so that it matches Earth's 365-day year. This allows the spacecraft to remain in a fixed position relative to the Earth and Sun.23

For IMAP, L1 is the ultimate "high ground."

Uninterrupted Solar View: Because L1 is always between Earth and the Sun, a spacecraft there never passes into Earth's shadow. It has a continuous, 24/7 view of the Sun, which is essential for monitoring the solar wind.24

Upstream Monitor: The solar wind flows from the Sun to the Earth. A spacecraft at L1 is "upstream" of Earth, meaning it encounters solar wind structures (like shocks or coronal mass ejections) roughly 30 to 60 minutes before they reach Earth. This makes L1 the ideal location for an early warning system.18

Quiet Environment: Far from the Earth's messy magnetosphere and radiation belts, L1 offers a pristine magnetic and particle environment, allowing for sensitive measurements of the subtle interstellar magnetic field.25

3.2 The Halo Orbit Strategy

While we speak of "arriving at L1," spacecraft rarely sit at the exact mathematical point, which is dynamically unstable—like balancing a pencil on its tip. Any slight perturbation would cause the spacecraft to drift away toward the Sun or Earth. Instead, IMAP utilizes a halo orbit.10

A halo orbit is a periodic, three-dimensional orbit that loops around the L1 point. Viewed from Earth, the spacecraft appears to move in a halo or circle around the Sun. This orbit is advantageous because it keeps the spacecraft out of the exact line of sight between Earth and the Sun, which is radio-noisy due to solar emissions. By orbiting around the L1 point, IMAP maintains a clear communication line with the Deep Space Network (DSN) on Earth while avoiding the intense solar interference that would occur if it were directly in front of the solar disk.26

3.3 The Journey and Arrival

The transit from Earth to L1 took approximately three and a half months.19 Following launch, the spacecraft entered a transfer orbit—a long, elliptical path that slowly climbed out of Earth's gravitational influence. During this "cruise phase," the operations team was far from idle. They activated the spacecraft's systems, deployed the solar arrays, and began the "commissioning" of the ten scientific instruments.19

Crucially, the instruments began collecting "first light" data during the journey. They measured interstellar dust and solar wind particles while still in transit, providing a baseline calibration for the mission.12

The culmination of this journey occurred on January 10, 2026. The APL operations team commanded a series of trajectory correction maneuvers (TCMs) using the spacecraft's hydrazine thrusters.19 These burns were critical; coming in too fast would cause the spacecraft to overshoot L1, while coming in too slow would result in it falling back toward Earth. The final insertion maneuver successfully nullified the drift velocity, locking IMAP into its halo orbit. As of January 12, 2026, the mission was declared to be in its operational orbit, ready to begin its primary science phase on February 1.19

Chapter 4: The Physics of the Boundary

4.1 The Solar Wind Interaction

To appreciate what IMAP is observing, we must delve into the physics of the heliospheric boundary. The solar wind is a plasma, a gas of protons and electrons. As it travels outward, its density decreases (expanding into a larger volume), but its velocity remains supersonic. Eventually, billions of kilometers from the Sun, this wind becomes too tenuous to push back the pressure of the interstellar medium.

This point of balance creates the termination shock. Here, the solar wind abruptly slows down, compressing and heating up. This is akin to water from a faucet hitting the bottom of a sink and spreading out in a turbulent, slower-moving sheet. Beyond the termination shock lies the heliosheath, a region of hot, turbulent plasma. Finally, the heliopause marks the boundary where solar material stops and interstellar material begins.3

4.2 Charge Exchange: The Key to ENA Imaging

How can IMAP, sitting at L1 near Earth, see a boundary that is 100 astronomical units (AU) away? The answer lies in a process called charge exchange.

The interstellar medium is not empty; it is filled with neutral atoms (mostly hydrogen and helium) from the galaxy. These neutral atoms are unaffected by magnetic fields and can drift freely through the heliopause and into the heliosheath. When a cold interstellar neutral atom collides with a hot proton (a hydrogen ion) in the heliosheath, a swap occurs: the neutral atom gives its electron to the proton.28

The result is transformative. The hot proton becomes a hot neutral hydrogen atom. Because it is now neutral, it is no longer trapped by the magnetic fields of the heliosheath. It retains its high speed and flies off in a straight line, preserving the velocity and direction it had at the moment of the collision.29 These are the Energetic Neutral Atoms (ENAs).

Some of these ENAs fly outward into the galaxy, but others fly inward, back toward the Sun. IMAP detects these inward-traveling ENAs. By mapping where they come from and how much energy they have, IMAP creates a "picture" of the hot plasma in the heliosheath. It is essentially a "proton camera," using neutral atoms instead of photons to image the invisible.1

4.3 The Ribbon and the Belt

The discovery of the IBEX Ribbon in 2009 was a watershed moment. This bright band of ENA emissions spans the sky and is aligned with the local interstellar magnetic field.8 Current theories suggest it is caused by a secondary charge exchange process: neutral solar wind atoms fly out, lose an electron to become ions again outside the heliopause, gyrate around the interstellar magnetic field lines, and then undergo another charge exchange to fly back inward as ENAs.7 This complex dance makes the Ribbon a direct tracer of the magnetic field outside our solar system.

In contrast, the Belt is a broader region of high-energy ENA emissions observed by the Cassini spacecraft (which had an ENA imager intended for Saturn's magnetosphere). The Belt seems to be related to the acceleration of particles inside the heliosphere.31 IMAP’s high-resolution imagers (IMAP-Hi and IMAP-Ultra) are designed to resolve the relationship between the narrow Ribbon and the broad Belt, determining if they are distinct features or parts of a continuous spectrum of particle interactions.31

4.4 The Bow Shock Controversy

For decades, textbooks stated that the solar system creates a bow shock as it moves through the galaxy, similar to the sonic boom of a supersonic jet. However, data from IBEX suggested that the solar system moves slower relative to the interstellar cloud than previously thought (about 52,000 mph or 23 km/s), which might be too slow to form a shock.32 Instead, there may only be a bow wave, a gentler piling up of material, similar to the wave ahead of a slow-moving boat.33

This distinction is crucial for understanding the filtration of cosmic rays. A strong bow shock would be a turbulent barrier, stripping away many cosmic rays. A bow wave is more permeable. IMAP will settle this debate by precisely measuring the speed, temperature, and direction of the interstellar neutral atoms entering the system, providing the definitive inputs needed to model the interaction.32

Chapter 5: Imaging the Invisible (The ENA Imagers)

IMAP’s "eyes" are its three ENA imagers, each tuned to a different energy range to peel back the layers of the heliosphere.

5.1 IMAP-Lo: The Interstellar Breeze

Lead Institution: University of New Hampshire.30

Energy Range: ~10 eV to 1 keV.30

Function: IMAP-Lo is designed to detect the lowest energy particles: the interstellar neutral atoms themselves and low-energy ENAs.

Technical Detail: This instrument is mounted on a pivot platform. This is a critical design feature. As the Earth (and IMAP) orbits the Sun, the apparent direction of the interstellar wind changes (due to aberration, similar to rain hitting a moving car's windshield). The pivot allows IMAP-Lo to track this wind continuously throughout the year.30

Science Goal: By measuring the exact flow direction and energy of neutral Helium, Oxygen, and Hydrogen atoms, IMAP-Lo will determine the precise velocity vector of the solar system through the galaxy and the temperature of the Local Interstellar Cloud.29

5.2 IMAP-Hi: The Structure of the Ribbon

Lead Institutions: Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), Southwest Research Institute (SwRI).16

Energy Range: ~0.4 keV to 16 keV.9

Function: IMAP-Hi bridges the gap between the low-energy neutrals and the high-energy cosmic rays. This is the "sweet spot" for the IBEX Ribbon emissions.

Technical Detail: Unlike IBEX-Hi, which had limited resolution, IMAP-Hi utilizes advances in detector technology to achieve significantly higher angular resolution (4 degrees vs IBEX's 7 degrees) and sensitivity.31 It uses a single-pixel detector design that scans the sky as the spacecraft spins.

Science Goal: IMAP-Hi will resolve the fine structure of the Ribbon. Is it a solid band, or is it made of fragmented filaments? Understanding this structure is key to validating the "secondary ENA" theory and mapping the interstellar magnetic field strength.9

5.3 IMAP-Ultra: The High-Energy Frontier

Lead Institution: Johns Hopkins APL.1

Energy Range: ~3 keV to 300 keV.37

Function: IMAP-Ultra looks at the highest energy ENAs. These particles originate from ions that have been accelerated to extreme speeds, likely at the termination shock or in the turbulent heliosheath.

Technical Detail: The instrument consists of two identical sensor heads. One looks 90 degrees to the spacecraft spin axis (scanning the ecliptic plane), and the other looks at 45 degrees. As the spacecraft spins, this geometry allows IMAP-Ultra to cover the entire celestial sphere.36 It uses "time-of-flight" technology to measure the speed of incoming atoms, distinguishing between hydrogen, helium, and oxygen.

Science Goal: IMAP-Ultra will image the "Belt" and provide the crucial link between the solar wind and cosmic rays. It essentially maps the "particle accelerators" of the outer solar system, showing where and how particles are being energized.37

Chapter 6: Sampling the Solar Wind (In-Situ Instruments)

To understand the ENAs coming from the boundary, we must understand the seed population going to the boundary. IMAP’s in-situ instruments turn the spacecraft into a high-precision weather station at L1.

6.1 SWAPI: Solar Wind and Pickup Ions

Lead Institution: Princeton University.39

Energy Range: 0.1 keV to 20 keV.39

Technical Detail: SWAPI is a "top-hat" electrostatic analyzer. It uses electric fields to filter particles by their energy-to-charge ratio. It is a descendant of the SWAP instrument on the New Horizons mission to Pluto.39

The Physics of Pickup Ions: This is SWAPI’s superpower. As interstellar neutral atoms drift into the solar system, they eventually get ionized by UV sunlight. Once ionized, the solar wind's magnetic field grabs them ("picks them up") and accelerates them outward. These Pickup Ions (PUIs) are distinct from the regular solar wind ions; they are hotter and have a different velocity distribution.

Significance: PUIs are the primary seed population for Anomalous Cosmic Rays. By measuring them at 1 AU, SWAPI allows scientists to predict the PUI population reaching the termination shock, providing the "boundary condition" for models of the heliosphere.35

6.2 SWE: Solar Wind Electrons

Lead Institution: Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL).25

Energy Range: 1 eV to 5 keV.42

Technical Detail: SWE measures the 3D distribution of electrons. Electrons are much lighter than protons and move much faster. They carry heat (thermal energy) from the Sun into the solar system.

Significance: SWE can distinguish between "halo" electrons (high energy) and "core" electrons (low energy). This distinction helps map the magnetic topology of the solar wind—specifically, whether magnetic field lines are open (connected to the Sun at only one end) or closed (loops). This is vital for understanding CMEs and space weather structures passing IMAP.25

6.3 CoDICE: The Bridge

Lead Institution: Southwest Research Institute (SwRI).43

Energy Range: Suprathermal ions (energies between solar wind and cosmic rays).35

Technical Detail: CoDICE (Compact Dual Ion Composition Experiment) combines two types of analyzers into one "paint bucket-sized" instrument. It measures the composition (mass) and charge of ions.

Significance: CoDICE fills the "energy gap." SWAPI sees the slow solar wind; HIT sees the fast cosmic rays. CoDICE sees the particles in between—the "suprathermal tails." These are the particles that have just begun the acceleration process. Studying them reveals the initial mechanisms of how a particle gets "injected" into a shock wave to become a cosmic ray.45

6.4 HIT: High-energy Ion Telescope

Lead Institution: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.46

Energy Range: 2 MeV to 50 MeV per nucleon.35

Technical Detail: HIT uses a stack of solid-state silicon detectors. When a high-energy particle hits the silicon, it deposits energy. By measuring the energy loss in each layer of the stack, HIT can determine the particle's species (from Hydrogen to Nickel) and its total energy.47

Significance: HIT measures Solar Energetic Particles (SEPs) ejected by solar flares. It is the primary "storm warning" instrument. When HIT detects a sudden spike in high-energy protons, it signals that a radiation storm is en route to Earth, triggering I-ALiRT warnings.48

Chapter 7: Fields, Dust, and Glow

7.1 MAG: The Magnetic Skeleton

Lead Institution: Imperial College London.35

Technical Detail: MAG consists of two fluxgate sensors mounted on a 1.8-meter boom. The boom is necessary to distance the sensors from the magnetic interference of the spacecraft's electronics. It measures the magnetic field vector with a resolution of 0.05 nT.49

Significance: Charged particles (solar wind, PUIs, cosmic rays) are slaves to the magnetic field; they spiral along field lines. You cannot understand particle motion without knowing the magnetic field orientation. MAG provides the "context" for every other particle instrument on board.50

7.2 IDEX: Analyzing Stardust

Lead Institution: LASP (University of Colorado).51

Technical Detail: IDEX (Interstellar Dust Experiment) is a dust impact mass spectrometer. It has a large effective target area (700 sq. cm) to catch rare dust grains. When a dust grain hits the target at high speed, it vaporizes and ionizes. IDEX uses an electric field to analyze the resulting ion cloud, determining the chemical composition of the dust.52

Significance: This is essentially a telescope that "tastes" the galaxy. It detects dust grains that were formed in the atmospheres of other stars and have drifted across the galaxy to reach us. IDEX will tell us what the local galaxy is made of—how much carbon, silicates, and iron exist in the Local Interstellar Cloud.54

7.3 GLOWS: Mapping the Helioglow

Lead Institution: Space Research Center of the Polish Academy of Sciences (CBK PAN).16

Technical Detail: GLOWS is a photometer tuned to the Lyman-alpha wavelength (121.6 nm). This is the ultraviolet light emitted by hydrogen atoms.

The Physics: Interstellar hydrogen atoms entering the solar system scatter sunlight at this wavelength, creating a faint "glow" across the sky.

Significance: By mapping this glow, GLOWS allows scientists to deduce the density and distribution of neutral hydrogen in the heliosphere. It also monitors the solar wind structure at high latitudes (the poles of the Sun) by observing how the solar wind ionizes the hydrogen, carving "holes" in the glow.55

Chapter 8: Real-Time Space Weather: I-ALiRT

8.1 The Societal Need for Space Weather Data

As our civilization becomes dependent on satellites for navigation (GPS), communication, and banking, and as power grids become more interconnected, the vulnerability to space weather increases. A massive Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) hitting Earth can induce geomagnetic currents that melt transformers and blackout cities. It can also strip the atmosphere, creating drag that de-orbits satellites, and expose astronauts to lethal radiation.50

8.2 The I-ALiRT Architecture

IMAP introduces a revolutionary capability: I-ALiRT (IMAP Active Link for Real-Time). Unlike typical science missions that store data and download it once a day, I-ALiRT maintains a continuous downlink of a subset of data.58

Instruments Involved: MAG, HIT, CoDICE, SWE, SWAPI.59

Mechanism: The spacecraft broadcasts this "beacon" signal continuously. It is picked up by a network of antennas around the globe—not just the specialized Deep Space Network (DSN), but also partner ground stations.59

Data Flow: The signal is routed to the IMAP Science Data Center at LASP, processed immediately using Amazon Web Services (AWS) cloud infrastructure, and distributed to NOAA and other forecasting centers.59

Impact: This provides a 15-to-45-minute warning before a solar wind structure detected at L1 hits Earth. This "heads-up" is critical for putting satellites into safe mode, diverting polar flights to avoid radiation, and configuring power grids to resist induced currents.18

Chapter 9: Institutional Collaboration and Legacy

9.1 A Partnership of Excellence

The success of IMAP relies on a complex web of partnerships managed by APL.

APL (Johns Hopkins): Project management, systems engineering, spacecraft bus, I-ALiRT, and IMAP-Ultra. APL’s role is the backbone of the mission, translating scientific requirements into flight hardware.1

Princeton University: The PI institution (Prof. David McComas). Princeton provides the scientific leadership and the SWAPI instrument. The university's involvement ensures the mission remains focused on answering the fundamental physics questions identified in the Decadal Survey.61

NASA Goddard: Program management and the HIT instrument.

Southwest Research Institute (SwRI): A powerhouse in space physics, SwRI built CoDICE and manages the payload systems engineering, ensuring all 10 instruments play nicely together.44

Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL): Leveraging their nuclear detection heritage to build the SWE and IMAP-Hi instruments.16

9.2 The Legacy of Discovery

IMAP is not an isolated mission; it is the successor to a lineage of explorers.

Voyager: The scouts that found the boundary.

Ulysses: The first mission to explore the heliosphere at high solar latitudes.

IBEX: The photographer that discovered the Ribbon.

Parker Solar Probe: The mission touching the Sun, explaining the origin of the solar wind that IMAP studies at 1 AU.

IMAP acts as the "connective tissue" between these missions. It uses the in-situ techniques of Voyager and Parker but applies them at L1, and it uses the remote sensing of IBEX but with the resolution to make sense of the Voyager data points.4

Furthermore, IMAP paves the way for the future Interstellar Probe, a proposed mission that would travel much faster than Voyager (up to 1000 AU) into the pristine interstellar medium. IMAP will define the target conditions for that probe, telling it what to expect and where to aim.62

Chapter 10: Conclusion

The arrival of the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe at the L1 Lagrange point on January 10, 2026, marks the beginning of a new era in heliophysics. No longer are we staring into the fog of the outer solar system with low-resolution cameras or relying on single point measurements from aging probes. IMAP provides us with a high-definition, multi-spectral view of our cosmic home.

By simultaneously measuring the solar wind leaving our neighborhood and the energetic atoms returning from the horizon, IMAP will solve the mysteries of the Ribbon, define the physics of the bow wave, and explain how the universe accelerates particles to relativistic speeds. Moreover, through I-ALiRT, it stands watch over our technological society, providing the vigilance necessary to thrive in a star system driven by a volatile sun.

As IMAP begins its three-year prime mission, it does more than map a boundary; it defines the context of our existence. It reveals the heliosphere not just as a magnetic bubble, but as a living, breathing membrane that connects our star to the galaxy beyond—a membrane that protects us, sustains us, and holds the secrets of our origins among the stars.

Table 1: Summary of IMAP Scientific Instruments

Instrument | Full Name | Lead Institution | Primary Measurement Target | Energy/Mass Range | Key Science Goal |

IMAP-Lo | Low-energy ENA Imager | UNH | Neutral Atoms (H, He, O, Ne) | ~10 eV – 1 keV | Determine velocity/temp of LISM; map interstellar wind. |

IMAP-Hi | High-energy ENA Imager | LANL / SwRI | Energetic Neutral Atoms | ~0.4 keV – 16 keV | Resolve the IBEX Ribbon structure and heliosheath plasma. |

IMAP-Ultra | Ultra-high energy ENA Imager | JHU APL | High Energy ENAs | ~3 keV – 300 keV | Image the "Belt"; link solar wind ions to cosmic rays. |

SWAPI | Solar Wind and Pickup Ion | Princeton | Solar Wind & Pickup Ions | 0.1 – 20 keV | Measure seed population for anomalous cosmic rays (PUIs). |

SWE | Solar Wind Electron | LANL | Solar Wind Electrons | 1 eV – 5 keV | Determine solar wind magnetic topology (open vs closed). |

CoDICE | Compact Dual Ion Composition | SwRI | Suprathermal Ions | PUI energies to ~MeV | Measure particle injection into acceleration mechanisms. |

HIT | High-energy Ion Telescope | NASA GSFC | Energetic Particles (SEP/GCR) | ~2 – 50 MeV/nucleon | Monitor radiation storms; study shock acceleration. |

MAG | Magnetometer | Imperial College | Interplanetary Magnetic Field | Dynamic range ±60,000 nT | Provide magnetic context for particle transport. |

IDEX | Interstellar Dust Experiment | LASP | Interstellar Dust Grains | Mass range 1–500 amu | Analyze chemical composition of galactic matter. |

GLOWS | GLObal Solar Wind Structure | CBK PAN | Lyman-alpha UV Glow | 121.6 nm | Map neutral hydrogen density and solar wind structure. |

Data compiled from IMAP technical overviews.9

Works cited

IMAP | Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.jhuapl.edu/destinations/missions/imap

Mission Science | Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) mission at Princeton, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/mission/science

Components of the Heliosphere - NASA, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.nasa.gov/image-article/components-of-heliosphere/

NASA's IMAP Mission to Study Boundaries of Our Home in Space, accessed January 13, 2026, https://science.nasa.gov/missions/nasas-imap-mission-to-study-boundaries-of-our-home-in-space/

NASA's Voyager 2 Probe Enters Interstellar Space, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/nasas-voyager-2-probe-enters-interstellar-space/

NASA's IBEX and Voyager spacecraft drive advances in outer heliosphere research, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.swri.org/newsroom/press-releases/the-nasa-ibex-voyager-spacecraft-drive-advances-outer-heliosphere-research

NASA's IBEX Observations Pin Down Interstellar Magnetic Field, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.nasa.gov/missions/ibex/nasas-ibex-observations-pin-down-interstellar-magnetic-field/

IBEX ribbon - Wikipedia, accessed January 13, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IBEX_ribbon

Interstellar MApping Probe (IMAP) mission concept: Illuminating the dark boundaries at the edge of our solar system, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www8.nationalacademies.org/ssbsurvey/detailfiledisplay.aspx?id=643&parm_

Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe - Wikipedia, accessed January 13, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interstellar_Mapping_and_Acceleration_Probe

NASA Selects Mission to Study Solar Wind Boundary of Outer Solar System, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.nasa.gov/news-release/nasa-selects-mission-to-study-solar-wind-boundary-of-outer-solar-system/

Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) mission at Princeton, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/

Meet IMAP leaders Dave McComas and Jamie Rankin - Princeton University, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.princeton.edu/news/2025/09/21/meet-imap-leaders-dave-mccomas-and-jamie-rankin

NASA Launches IMAP Mission to Study the Heliosphere and Better Understand Space Weather | Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.jhuapl.edu/news/news-releases/250924-imap-launch

IMAP Mission Partner Organizations - Princeton University, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/partner-organizations

IMAP Mission Partners - Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe - Princeton University, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/home/imap-mission-partners

International Partnership Powers IMAP Mission Through Collaboration - NASA Science, accessed January 13, 2026, https://science.nasa.gov/blogs/imap/2025/08/08/international-partnership-powers-imap-mission-through-collaboration/

NASA's IMAP Suite of Instruments, accessed January 13, 2026, https://science.nasa.gov/blogs/imap/2025/09/24/nasas-imap-suite-of-instruments/

NASA's IMAP Reaches Orbit to Start Study of Heliosphere and Space Weather, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.jhuapl.edu/news/news-releases/260112-imap-arrives-l1

Mission Timeline | Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) mission at Princeton, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/spacecraft/mission-timeline

ESA - L1, the first Lagrangian Point - European Space Agency, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/L1_the_first_Lagrangian_Point

What are Lagrange Points? - NASA Science, accessed January 13, 2026, https://science.nasa.gov/solar-system/resources/faq/what-are-lagrange-points/

Lagrange point - Wikipedia, accessed January 13, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lagrange_point

Lagrange Points: An Orbital Parking Spot for Satellites | NESDIS, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/our-satellites/lagrange-points-orbital-parking-spot-satellites

Solar Wind Electron (SWE) Technical Overview | Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) mission at Princeton, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/spacecraft/instruments/solar-wind-electron-swe/swe-technical-overview

IMAP Traveling to L1 - NASA SVS, accessed January 13, 2026, https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/14888/

L3Harris-Powered IMAP Spacecraft Set to Begin Interstellar Mapping Mission, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.l3harris.com/newsroom/editorial/2025/09/l3harris-powered-imap-spacecraft-set-begin-interstellar-mapping-mission

Energetic neutral atom - Wikipedia, accessed January 13, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energetic_neutral_atom

Chapter: 2 Science Summary: The Interaction of the Solar Wind and the Local Interstellar Medium, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.nationalacademies.org/read/11135/chapter/4

IMAP-Lo Technical Overview - Princeton University, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/spacecraft/instruments/imap-lo/imap-lo-technical-overview

IMAP (Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe) - eoPortal, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.eoportal.org/satellite-missions/imap

New IBEX data show heliosphere's long-theorized bow shock does not exist, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.swri.org/newsroom/press-releases/new-ibex-data-show-the-heliosphere-long-theorized-bow-shock-does-not-exist

accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.swri.org/newsroom/press-releases/new-ibex-data-show-the-heliosphere-long-theorized-bow-shock-does-not-exist#:~:text=%22While%20bow%20shocks%20certainly%20exist,it%20glides%20through%20the%20water%2C%22

Bow-shock no-show shocks astronomers - Physics World, accessed January 13, 2026, https://physicsworld.com/a/bow-shock-no-show-shocks-astronomers/

Interstellar Mapping And Acceleration Probe: The NASA IMAP Mission - PubMed Central, accessed January 13, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12575477/

IMAP-Ultra - Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe - Princeton University, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/spacecraft/instruments/imap-ultra

The IMAP-Ultra Energetic Neutral Atom (ENA) Imager - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed January 13, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12738616/

IMAP-Ultra Technical Overview - Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/spacecraft/instruments/imap-ultra/imap-ultra-technical-overview

Details for Instrument SWAPI - WMO OSCAR, accessed January 13, 2026, https://space.oscar.wmo.int/instruments/view/swapi

Charged Particle-Sensing Instrument Installed on IMAP - NASA Science, accessed January 13, 2026, https://science.nasa.gov/blogs/imap/2024/11/21/charged-particle-sensing-instrument-installed-on-imap/

Solar Wind and Pickup Ions (SWAPI) | Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) mission at Princeton, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/spacecraft/instruments/solar-wind-and-pickup-ions-swapi

Details for Instrument SWE (IMAP) - WMO OSCAR, accessed January 13, 2026, https://space.oscar.wmo.int/instruments/view/swe_imap

IMAP Instrument Installations Complete - NASA Science, accessed January 13, 2026, https://science.nasa.gov/blogs/imap/2025/01/16/imap-instrument-installations-complete/

NASA's Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe Mission Enters Design Phase, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.swri.org/newsroom/press-releases/nasa-s-interstellar-mapping-acceleration-probe-mission-enters-design-phase

Compact Dual Ion Composition Experiment (CoDICE) Technical Overview - IMAP, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/spacecraft/instruments/compact-dual-ion-composition-experiment-codice/codice-technical-overview

High-energy Ion Telescope (HIT) | Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) mission at Princeton, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/spacecraft/instruments/high-energy-ion-telescope-hit

High-energy Ion Telescope (HIT) Technical Overview | Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) mission at Princeton, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/spacecraft/instruments/high-energy-ion-telescope-hit/hit-technical-overview

New Instrument to Measure High-energy Solar Particles as Part of NASA Mission | BNL Newsroom - Brookhaven National Laboratory, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.bnl.gov/newsroom/news.php?a=221926

Magnetometer (MAG) - MAVEN - Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, accessed January 13, 2026, https://lasp.colorado.edu/maven/science/instrument-package/mag/

Magnetometer (MAG) Technical Overview | Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) mission at Princeton, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/spacecraft/instruments/magnetometer-mag/mag-technical-overview

Interstellar Dust Experiment (IDEX) Technical Overview - IMAP, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/spacecraft/instruments/interstellar-dust-experiment-idex/idex-technical-overview

Interstellar Dust Experiment (IDEX) | Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) mission at Princeton, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/spacecraft/instruments/interstellar-dust-experiment-idex

Details for Instrument IDEX - WMO OSCAR, accessed January 13, 2026, https://space.oscar.wmo.int/instruments/view/idex

The Interstellar Dust Experiment (IDEX) onboard the IMAP Mission: Performance and First-light Results, accessed January 13, 2026, https://agu.confex.com/agu/agu25/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/1886553

Global Solar Wind Structure (GLOWS) Technical Overview - IMAP - Princeton University, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/spacecraft/instruments/global-solar-wind-structure-glows/glows-technical-overview

NASA's IMAP Mission Captures 'First Light,' Looks Back at Earth, accessed January 13, 2026, https://science.nasa.gov/science-research/heliophysics/nasas-imap-mission-captures-first-light-looks-back-at-earth/

Solar Wind Electron (SWE) - Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/spacecraft/instruments/solar-wind-electron-swe

Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) - NASA Science, accessed January 13, 2026, https://science.nasa.gov/mission/imap/

I-ALiRT Space Weather - IMAP Science Data Center, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap-mission.com/ialirt

I-ALiRT System for Forecasting Space Weather - ucar | cpaess, accessed January 13, 2026, https://cpaess.ucar.edu/abstract-sww-2024/i-alirt-system-forecasting-space-weather

Meet IMAP Leaders Dave McComas and Jamie Rankin - Princeton University, accessed January 13, 2026, https://imap.princeton.edu/news/meet-imap-leaders-dave-mccomas-and-jamie-rankin

Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP): A New NASA Mission - Space Physics at Princeton, accessed January 13, 2026, https://spacephysics.princeton.edu/sites/g/files/toruqf1376/files/media/mccomas_etal_2018_imap_new_nasa_mission.pdf

Comments