The Efficacy-Effectiveness Gap: A Critical Re-evaluation of Clinical Validity in AI-Driven Robotic Surgical Systems

- Bryan White

- 9 hours ago

- 13 min read

Abstract

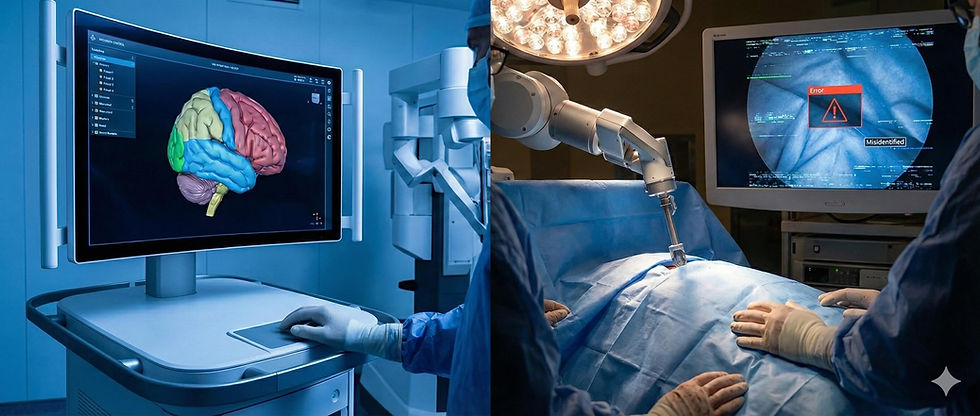

In February 2026, the medical community was shaken by a comprehensive investigation published by Reuters, which detailed a systemic failure of artificial intelligence technologies in the operating room. Titled "As AI enters the operating room, reports arise of botched surgeries and misidentified body parts," the report brought into sharp focus the "efficacy-effectiveness gap" plaguing modern surgical robotics.1 While the promise of "digital surgery" was predicated on superhuman precision and the augmentation of human capability, the reality revealed a disturbing pattern of algorithmic hallucinations, semantic segmentation failures, and latency-induced tissue trauma. This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the crisis, dissecting the technical architectures of the systems involved—from the computer vision models of the "Lumina" surgical assistant to the haptic feedback loops of the Da Vinci 5. By synthesizing data from the Reuters investigation, legal filings, and technical literature, we explore how the rush to market, driven by a $20 billion industry projection, outpaced the necessary safety validation for high-stakes biological environments.3 The analysis concludes with a critical examination of the regulatory blind spots in the FDA’s 510(k) pathway and offers a forward-looking perspective on the necessity of "Explainable AI" (XAI) in future surgical platforms.

1. Introduction: The Digital Transformation of the Operating Theater

The trajectory of modern surgery has been defined by a relentless pursuit of visibility and control. From the introduction of the laparoscope in the 1980s to the robotic revolution of the early 2000s, each technological leap has distanced the surgeon’s hands from the patient while simultaneously bringing their vision closer to the pathology. The 2020s were poised to be the decade of "Cognitive Surgery," a paradigm shift where the surgical robot would evolve from a passive master-slave telemanipulator into an active, intelligent partner capable of perceiving the surgical field and guiding decision-making.4

By 2025, the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into surgical workflows had become ubiquitous in top-tier academic centers and was rapidly expanding to community hospitals. Systems like Intuitive Surgical’s Da Vinci 5, Medtronic’s Hugo, and Johnson & Johnson’s Ottava platform promised to democratize surgical excellence.5 These platforms utilized advanced computer vision to overlay critical anatomical structures—nerves, ureters, and blood vessels—onto the surgeon's viewfinder, effectively granting them X-ray vision.

However, on February 9, 2026, the Reuters investigation shattered the veneer of infallibility surrounding these technologies. The report documented a series of catastrophic failures where AI assistants, rather than preventing errors, actively contributed to them. The investigation highlighted cases of "botched surgeries" where AI systems misidentified body parts, leading surgeons to transect critical ducts or remove healthy organs.3 The crisis was not merely a series of isolated accidents but a revelation of fundamental flaws in how deep learning models are trained, validated, and deployed in the chaotic, high-stakes environment of live surgery.

This article aims to deconstruct the technical and clinical dimensions of the 2026 crisis. It moves beyond the sensational headlines to analyze the specific failure modes of computer vision in the presence of surgical smoke, the physics of haptic feedback latency, and the cognitive psychological phenomenon of "automation bias" that led experienced surgeons to override their training in favor of algorithmic suggestions.

2. The Reuters Investigation: Anatomy of the Catastrophe in Robotic Surgical Systems

The Reuters report of February 2026 served as a catalyst for a global re-evaluation of medical AI. It aggregated adverse event reports, lawsuit filings, and whistleblower testimonies to paint a picture of an industry that had scaled too fast, relying on "substantial equivalence" regulatory clearances rather than rigorous clinical trials for novel software functions.3

2.1 The "Misidentified Body Part" Phenomenon

The central finding of the investigation was the prevalence of identification errors. In traditional surgery, misidentification is a human cognitive error, often resulting from fatigue or anatomical distortion. In the era of AI, misidentification became a "semantic segmentation" error. The report detailed instances where AI overlays, designed to highlight the common bile duct (a critical structure carrying bile from the liver) to prevent injury during gallbladder removal, erroneously labeled it as the cystic duct (the structure safe to cut).3

In one particularly egregious case, an AI system known as the "Lumina" surgical assistant—a third-party software integrated into robotic platforms—failed to distinguish between the ureter and a blood vessel during a pelvic procedure.8 The system’s confidence score remained high, creating a false sense of security for the operating surgeon, who subsequently transected the ureter, leading to severe long-term complications for the patient.

2.2 Hallucinations and "Invented" Organs

Perhaps the most disturbing revelation was the capacity for generative AI models to "hallucinate" anatomical structures. The nonprofit ECRI Institute had already flagged the "misuse of AI chatbots" and generative tools as a top health hazard for 2026, warning that these systems could "invent body parts".10 The Reuters investigation confirmed this fear, citing cases where preoperative planning software, powered by generative adversarial networks (GANs), reconstructed 3D models of patients that included organs that were not present or excluded pathologies that were.

In one cited instance, a system hallucinated an "accessory spleen" in a patient undergoing a splenectomy. The surgeon, guided by the AI-generated navigation map, spent valuable intraoperative time searching for a structure that did not exist, prolonging anesthesia time and increasing the risk of infection.3 These hallucinations stem from the fundamental nature of generative AI, which is designed to produce plausible-looking data based on statistical likelihoods rather than to verify ground truth.

2.3 The "Wrong Patient" Data Linkage Failure

While robotic failures dominated the headlines, the investigation also uncovered a quieter, yet equally deadly, class of errors: administrative AI failures. As hospitals raced to automate their Electronic Health Records (EHR) and scheduling systems, AI agents tasked with linking imaging data to patient files began to falter.

The report highlighted a tragic case at St. Jude Medical Center in Fullerton, California (referencing a historical pattern of similar errors), where a patient allegedly underwent a nephrectomy (kidney removal) based on the CT scan of another patient.11 The AI scheduling agent had failed to flag the discrepancy in the patients' dates of birth, treating the imaging file as a match based on name similarity. This "wrong patient" error, facilitated by the removal of human redundancy checks, underscores the fragility of automated administrative workflows in healthcare.12

3. Technical Failure Mode I: The Vision Crisis

To understand why these systems failed, one must delve into the architecture of surgical computer vision. The dominant methodology in 2026 was Semantic Segmentation, a process where a deep learning model (typically a Convolutional Neural Network or Vision Transformer) classifies every pixel in a video frame.13

3.1 The Semantic Segmentation Architecture

The standard architecture for these tasks is the U-Net, developed originally for biomedical image segmentation. It consists of an "encoder" path that compresses the image to extract high-level features (texture, shape) and a "decoder" path that expands it back to the original resolution to create a pixel-perfect mask.13

In a controlled environment, such as a training dataset like Cholec80 (a benchmark dataset of gallbladder surgeries), these models achieve high accuracy, often exceeding 90% Intersection-over-Union (IoU).14 However, the Reuters investigation revealed that performance in the wild—the "effectiveness" phase—was drastically lower.

3.2 The Impact of Surgical Smoke and Debris

A primary antagonist in the computer vision failure was surgical smoke. High-energy instruments used for cutting and cauterizing tissue generate plumes of smoke that obscure the visual field.

Scattering and Occlusion: Smoke particles scatter light, reducing contrast and altering the color profile of the tissue.

Algorithmic Confusion: Most training datasets are curated to include clear views. When an AI model trained on clear images encounters dense smoke, it faces an "out-of-distribution" input.

The "White Pixel" Problem: Research has shown that smoke, which often appears white or gray, can be misinterpreted by the neural network as connective tissue or nerve fibers, which also appear white.15

In the "botched" surgeries cited by Reuters, the AI overlays did not disappear when smoke filled the cavity; instead, they became erratic. The system, forced to make a prediction, hallucinated a "safe" cutting plane through the smoke, leading the surgeon astray.3

3.3 Anatomical Variance and the "Average" Patient

AI models are statistical engines; they learn what an "average" gallbladder or ureter looks like. They struggle with atypical anatomy. The investigation noted that failures were disproportionately high in cases involving anatomical anomalies or severe inflammation (cholecystitis), which distorts the usual visual landmarks.

In these cases, the AI attempts to fit a "standard" map onto a "non-standard" territory. A surgeon, seeing inflammation, knows to proceed with extreme caution or convert to open surgery. The AI, lacking this contextual understanding or "metacognition" (knowing what it doesn't know), continues to project confident, yet incorrect, overlays.16

4. Technical Failure Mode II: The Haptic Feedback Loop

While vision provides the roadmap, touch provides the warning system. The promise of the 2026 generation of robots—specifically the Da Vinci 5 and comparable systems—was the integration of high-fidelity haptic feedback.5 Unlike earlier systems that relied on visual cues, these robots utilized sensors to transmit the physical sensation of tissue resistance back to the surgeon’s hands.

4.1 The Physics of Teleoperation Latency

Teleoperation relies on a continuous loop of data:

Master Input: The surgeon moves the controller.

Transmission: The signal travels to the robot.

Slave Action: The robot moves.

Force Sensing: The robot measures resistance.

Feedback Transmission: The force data travels back to the console.

Haptic Display: The controller resists the surgeon's hand.

For this illusion of physical connection to work, the latency (delay) must be minimal. Research indicates that haptic feedback latency must be below 50 milliseconds to prevent the user from perceiving a disconnect.17

4.2 The "Overshoot" Phenomenon

The Reuters report documented injuries consistent with latency-induced overshoot. When latency exceeds the 50ms threshold—due to network congestion, signal processing delays, or heavy AI computation loads—the surgeon’s hand moves faster than the robot can provide feedback.

The Mechanism of Injury: The surgeon pushes the instrument forward. The robot encounters tissue, but the "resistance" signal is delayed by 100ms or more. The surgeon, feeling no resistance yet, continues to push. By the time the feedback arrives, the robot has already driven the instrument millimeters past the intended stop point.

Clinical Consequence: In delicate tissues like the bowel or blood vessels, a few millimeters of overshoot is the difference between a successful dissection and a perforation. The report cited cases of hemorrhage and organ perforation directly linked to these "micro-crashes" in the control loop.3

4.3 Network Jitter and Packet Loss

The problem was exacerbated in hospitals using wireless or cloud-based processing for their AI tools. While 5G networks promised ultra-low latency, the reality of hospital infrastructure often involved "jitter"—variation in latency. Sudden spikes in lag caused the robotic response to become jerky or unpredictable, leading to tissue tearing.19

5. The Human Factor: Automation Bias and De-skilling

The introduction of AI did not just change the technology; it changed the surgeon. The investigation revealed profound psychological shifts in the operating room, centered on the concept of Automation Bias.

5.1 The Crisis of Confidence

Automation bias is the tendency for humans to favor suggestions from automated decision-making systems, even when they contradict their own sensory information. Surgeons interviewed for the Reuters report described a "crisis of confidence." When their own eyes suggested a structure was a blood vessel, but the $2 million AI system labeled it as safe connective tissue, they hesitated.

In high-stress environments, the cognitive load is high. The AI offers a "cognitive offload"—a shortcut. Trusting the machine becomes the path of least resistance. This bias was identified as a contributing factor in the severing of common bile ducts; the green overlay provided a false "permission structure" for the surgeon to cut.3

5.2 De-skilling of the Next Generation

A longer-term concern raised by the report was the de-skilling of surgical residents. Trainees who learned to operate with "GPS" overlays struggled to identify anatomical planes when the system was disabled or unavailable. One senior surgeon noted that residents were becoming "screen-dependent," lacking the tactile and visual intuition developed by previous generations who operated without digital augmentation.20

6. Industry Landscape: The Arms Race

The rush to deploy these immature technologies was driven by a fierce commercial arms race. The global surgical robotics market, valued at over $20 billion, had become a battleground for medical device giants.3

6.1 The Major Players

Intuitive Surgical: The market leader with its Da Vinci ecosystem. In 2026, the Da Vinci 5 was the flagship, boasting "10,000x the computing power" of its predecessor, the Xi. While this power enabled advanced features, it also introduced complexity and new failure modes related to data processing loads.5

Medtronic: The Hugo system emphasized modularity and data analytics, integrating "Digital Surgery" capabilities to record and analyze surgical steps. However, the integration of these analytics into real-time decision support proved fraught with challenges.6

Johnson & Johnson: The Ottava system, designed as a soft-tissue robot with a unified architecture, aimed to revolutionize the market. Its "zero-footprint" design and deep integration with the Ethicon digital ecosystem were major selling points, but it too faced scrutiny regarding the validation of its AI components.7

6.2 The "Lumina" Failure

The report specifically highlighted the failure of the "Lumina" surgical assistant. While distinct from the "Lumina Networks" business failure of 2020, the 2026 "Lumina" AI incident became a case study in proprietary software failure.8 Marketed as a "universal" AI assistant compatible with multiple robotic platforms, Lumina's algorithms failed to generalize across different camera systems and lighting conditions, leading to the misidentification errors cited in the Reuters investigation.

7. Regulatory and Legal Fallout

How did these systems reach the market with such critical flaws? The answer lies in the regulatory framework of the United States FDA.

7.1 The 510(k) Loophole

The majority of these AI tools were cleared via the 510(k) pathway, which requires a device to be "substantially equivalent" to a predicate device already on the market.3

The Flaw: Manufacturers argued that their AI segmentation tools were equivalent to standard surgical monitors—they both "display images." This ignored the fundamental difference: the AI was not just displaying; it was interpreting.

Clinical Trials: Unlike new drugs, which require rigorous randomized controlled trials (RCTs), many of these software updates were released with limited clinical validation, often performed on static datasets rather than in live, randomized surgical trials.

7.2 Liability and the "Black Box"

The legal aftermath of the botched surgeries has been chaotic.

Surgeon vs. Manufacturer: Manufacturers argued that the AI was merely "assistive" and that the surgeon (the "learned intermediary") remained the final decision-maker.24 However, plaintiffs argued that the "inaccurate overlays" constituted a product design defect that actively misled the surgeon.

The Call for "Flight Recorders": The opacity of the AI's decision-making—the "Black Box" problem—hindered accident investigation. In response, there is a growing movement to mandate "OR Black Boxes", systems that record not just video but the internal logic states of the AI, to adjudicate liability and improve safety.25

8. Data Representation: Comparative Analysis of Failure Modes

To understand the scale and nature of these errors, we can categorize the primary failure modes identified in the 2026 investigation.

Failure Mode | Mechanism of Action | Technical Cause | Clinical Consequence |

Semantic Segmentation Error | Mislabeling of anatomy (e.g., Bile Duct vs. Cystic Duct). | Low IoU scores in "noisy" environments (smoke, blood); training data bias. | Transection of critical ducts; bile leak; vascular injury. |

Haptic Overshoot | Robot moves further than intended due to delayed feedback. | Latency >50ms in the force-feedback loop; network jitter. | Organ perforation; tissue tearing; hemorrhage. |

Generative Hallucination | AI "invents" or "removes" structures in 3D models. | Generative model confabulation; statistical completion of missing data. | Unnecessary exploration; missed pathology (e.g., accessory spleen). |

Administrative Linkage Error | Surgery planned for the wrong patient. | AI failure to cross-check identifiers (DOB, MRN) in EHR linkage. | Wrong-patient surgery; removal of healthy organs. |

Table 1: Classification of AI-Driven Surgical Errors identified in the Reuters 2026 Investigation.

9. Future Directions: From "Black Box" to "Glass Box"

The crisis of 2026 was a painful inflection point. It demonstrated that the "move fast and break things" ethos of Silicon Valley is incompatible with the "do no harm" ethos of medicine. The path forward requires a fundamental rethinking of how surgical AI is built and regulated.

9.1 Explainable AI (XAI)

Future systems must move beyond simple overlays to Explainable AI. Instead of just highlighting a duct, the system should provide a confidence score and the rationale for its decision (e.g., "Identified as cystic duct due to connection with gallbladder neck; Confidence: 85%"). If visibility is poor due to smoke, the AI should default to a "System Blind" state rather than guessing.25

9.2 Synthetic Data and Simulation

To address the data gaps regarding smoke and anomalies, researchers are turning to synthetic data. Using physics-based rendering engines, developers can create photorealistic videos of rare complications—severed arteries, massive smoke plumes, anomalous anatomy—to train AI models on scenarios they rarely see in real life but must handle correctly.27

9.3 The Human-in-the-Loop Mandate

Finally, the industry is shifting toward a "Human-in-the-Loop" validation standard. Regulatory bodies are moving to require that AI tools be tested not just for algorithmic accuracy, but for human-system performance. A tool is only safe if it makes the surgeon safer. If an accurate AI causes distraction or automation bias that leads to errors, it is clinically defective.

10. Conclusion

The Reuters investigation of February 9, 2026, will be remembered as a critical moment in the medical AI industry. The transition of AI from the computer lab to the operating room has been revealing deep fissures in our technological readiness and regulatory oversight. The "botched" surgeries and misidentified bodies were not merely accidents; they were the inevitable result of deploying probabilistic systems into deterministic, high-stakes environments without adequate guardrails. Parametric AI, and the Large Language Models (LLMs) that employ its statistical methods, will always have risks if they remain unsupervised by human design and intervention.

As we look to the future, the role of AI in surgery remains promising but must be tempered with humility. The robotic platforms of tomorrow—whether from Intuitive, Medtronic, or new entrants—must prioritize robustness over novelty, and transparency over opacity. Until the "efficacy-effectiveness gap" is closed, the surgeon’s eye and hand must remain the ultimate arbiter of safety in the operating room. For the time being, human oversight is the key.

Works cited

/r/Technology - Reddit, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.reddit.com/r/technology/hot/

The Source | Washington University in St. Louis, accessed February 9, 2026, https://source.washu.edu/

When the Algorithm Holds the Scalpel: Inside the Alarming Rise of ..., accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.webpronews.com/when-the-algorithm-holds-the-scalpel-inside-the-alarming-rise-of-ai-related-surgical-failures/

Full article: Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: A Narrative Review of Recent Clinical Applications, Implementation Strategies, and Challenges, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2147/JHL.S553748

Da Vinci Robotic Surgical Systems - Intuitive, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.intuitive.com/en-gb/products-and-services/da-vinci

Digital Surgery | Medtronic (NZ), accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.medtronic.com/covidien/en-nz/products/digital-surgery.html

Johnson & Johnson Submits OTTAVA™ Robotic Surgical System to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.jnj.com/media-center/press-releases/johnson-johnson-submits-ottava-robotic-surgical-system-to-the-u-s-food-and-drug-administration

Holding AI Accountable: Addressing AI-Related Harms Through Existing Tort Doctrines, accessed February 9, 2026, https://lawreview.uchicago.edu/online-archive/holding-ai-accountable-addressing-ai-related-harms-through-existing-tort-doctrines

Artificial Intelligence in dentistry: potential ethical considerations – DDS News & Blog, accessed February 9, 2026, https://news.digital-dentistry.org/report/artificial-intelligence-in-dentistry-potential-ethical-considerations/

AI | MedTech Dive, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.medtechdive.com/topic/ai/

Doctor Removes Wrong Kidney: A Reminder About Wrong-Site Surgeries - FindLaw, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.findlaw.com/legalblogs/personal-injury/doctor-removes-wrong-kidney-a-reminder-about-wrong-site-surgeries/

5 Ways Surgery Errors Can Lead to Lawsuits - FindLaw, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.findlaw.com/legalblogs/personal-injury/5-ways-surgery-errors-can-lead-to-lawsuits/

Evaluating Deep Learning-Based Nerve Segmentation in Brachial Plexus Ultrasound Under Realistic Data Constraints - arXiv, accessed February 9, 2026, https://arxiv.org/html/2602.00763v1

Artificial intelligence for surgical scene understanding: a systematic ..., accessed February 9, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12820105/

SurgiATM: A Physics-Guided Plug-and-Play Model for Deep Learning-Based Smoke Removal in Laparoscopic Surgery - arXiv, accessed February 9, 2026, https://arxiv.org/html/2511.05059v2

MITEA: A dataset for machine learning segmentation of the left ventricle in 3D echocardiography using subject-specific labels from cardiac magnetic resonance imaging - Frontiers, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cardiovascular-medicine/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2022.1016703/full

Brain functional connectivity under teleoperation latency: a fNIRS study - Frontiers, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2024.1416719/full

Development of an Augmented Reality Surgical Trainer for Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery - MDPI, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/15/7/3532

Telementoring for surgical training in low-resource settings: a ..., accessed February 9, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12394307/

Robots in the Operating Room: 7 Key Facts About AI Surgery Robots in 2025 - Liv Hospital, accessed February 9, 2026, https://int.livhospital.com/robots-in-the-operating-room-7-key-facts-about-ai-surgery-robots-in-2025/

Da Vinci Robotic Surgical Systems - Intuitive, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.intuitive.com/en-us/products-and-services/da-vinci

Johnson & Johnson MedTech Receives IDE Approval for OTTAVA™ Robotic Surgical System, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.jnj.com/media-center/press-releases/johnson-johnson-medtech-receives-ide-approval-for-ottava-robotic-surgical-system

378 Startup Failure Post Mortems by CB Insights | PDF - Scribd, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.scribd.com/document/783297533/378-Startup-Failure-Post-Mortems-by-CB-Insights

© 2022 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 1 25 Va. J.L. & Tech. 38 Barbara Pfeffer Billauer Copyr, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.kiip.re.kr/webzine/2204/file/KIIP43_file3.pdf

AI in hand surgery: hype or helpful? A comprehensive survey of emerging technologies, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.oaepublish.com/articles/2347-9264.2025.80

Black Box Technology Shines Light on Improving OR Safety, Efficiency | ACS, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.facs.org/for-medical-professionals/news-publications/news-and-articles/bulletin/2023/july-2023-volume-108-issue-7/black-box-technology-shines-light-on-improving-or-safety-efficiency/

Will your next surgeon be a robot? Autonomy and AI in robotic surgery - PMC, accessed February 9, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12836364/

Comments